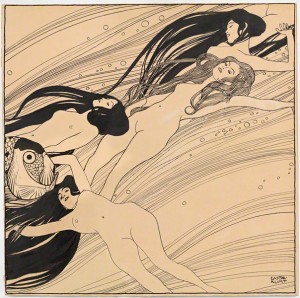

Fish Blood, 1897–98, Gustav Klimt. Brush and black ink, black chalk, heightened with white. Private collection, courtesy Galerie St. Etienne, New York

Gustav Klimt’s paintings, like his ornate and gilded “The Kiss,” are seemingly ubiquitous, printed on posters, mugs, notebooks, T-shirts. But we don’t really know his work, said Lee Hendrix, senior curator of drawings at the Getty Museum, where “Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line” opened on July 3 and continues through Sept. 23.

We can best learn about Klimt’s work through his drawings, Hendrix noted at a press preview of the exhibit, which beautifully traces the evolution of the Viennese master draftsman from academic realist in the mid-1880s to radical modernist in the early-20th century.

Featuring more than 100 drawings, many of which have never been exhibited in North America, this first retrospective fully dedicated to Klimt’s drawings was organized with the Albertina Museum, Vienna, to mark the 150th anniversary of the artist’s birth.

For Klimt, drawing was a daily practice (approximately 4,000 of his drawings survive). Working with live models, in particular the female nude, he developed his signature themes of human suffering, the struggle for love and happiness, and the cycle of life. As Dr. Marian Bisanz-Prakken, curator of drawings at the Albertina Museum, said during the press tour, Klimt’s work asks the question “What is the essence of life?” and explores that mystery in pure line.

Even the curators expressed amazement about the exceptionally intricate “Allegory of Sculpture,” one of Klimt’s early works with traditional modeling, light and shadow, which they had to view with a magnifying lens to discover its most subtle details. This piece is one of numerous highlights in the show.

“Fishblood” is another, a work influenced by Japanese art, eschewing three-dimensional space, and created during the early years of the Secession movement, which Klimt led. The exhibit continues with the controversial, rejected Faculty paintings and the ambitious “Beethoven Frieze,” both of which demonstrate Klimt’s changing approach to the human form. He moved toward the pure linear nude which could best capture the most raw and intense human emotions or “nuda veritas,” the naked truth of humanity, Hendrix noted.

Yet another highlight is a monumental transfer drawing of the “Three Ages of Women,” which became a famous painting. The final room of the exhibit is filled with images in which Klimt captured women floating in erotic states, representing an “idealized state of being” and “extreme expression of self-absorption,” Hendrix explained. In this later work, his style has changed from smooth, flowing lines to nervous, broken lines. In the particularly exquisite “Standing Figure Wrapped in a Kimono,” Klimt creates a “symphonic vocabulary of dots, dashes and circles,” Hendrix said.

“Gustav Klimt: The Magic of Line” ends with a quote by Max Eisler from “Klimt: The Aftermath” which says, “Klimt the draftsman is a completely independent master and without equal in this field.” Indeed, it’s a statement you’ll find proven by the works on display. Add to that thought the fact that Bisanz-Prakken could think of no real heirs or descendants of Klimt in contemporary art, and this is an exhibit not to be missed.

Among many related exhibits and events to enjoy are a lecture by Bisanz-Prakken titled “Gustav Klimt: Drawing as a Guiding Principle” at the Getty Museum on Sunday, July 8, and a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony by the LA Philharmonic and LA Master Chorale at the Hollywood Bowl, featuring video imagery by Herman Kolgen inspired by Klimt’s “Beethoven Frieze” to accompany the famous “Ode to Joy” finale, on Tuesday, July 10.

For more information, visit https://www.getty.edu/art/exhibitions/klimt/.