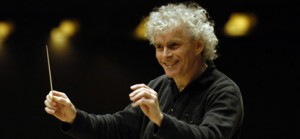

On Saturday night, the Berlin Philharmonic, under the baton of its music director, Sir Simon Rattle, gave LA concertgoers something to be grateful for this Thanksgiving, a transcendent performance of Mahler’s Symphony No. 7 in E minor. Also on the program was a brief composition for a small ensemble of 15 instruments by Pierre Boulez titled Éclat.

German orchestras are notoriously punctual and walk out at exactly the time the concert is supposed to begin. But the Berlin Philharmonic was on LA time, walking onstage more than five minutes late, even though, in typical German fashion, they all walked on together at the same time. For what it’s worth, one couldn’t help but notice the preponderance of male musicians. This reviewer only counted about 14 females in the orchestra of more than 100 musicians.

Rattle opened the concert with the Boulez, which was first performed at UCLA by members of the LA Phil in 1965 with the composer conducting. It was an interesting choice for an opening to a concert of Mahler’s seventh symphony, which, for all practical purposes, was the show. Éclat’s minimalistic structure contrasted dramatically with the enormity and rich tapestry of the Mahler. One thing they had in common, however, was the scoring for guitar and mandolin. Rattle and the 15 musicians very adeptly transformed Boulez’s intention to convey resonances created by the 15 instruments. Nevertheless, it probably wasn’t fair to Boulez or his work to pair it with the Mahler.

That said, once the Berlin Philharmonic began the Mahler, it was obvious that this is still one of the two or three top orchestras in the world. Moreover, with Rattle they have remained as good as they were under Claudio Abbado and Herbert von Karajan before him. Their sound, aided by the Disney Hall acoustics, jumped out at the listener. It was strong and tight, and every phrase in Mahler’s expansive symphonic landscape was nuanced. The musicians behaved as one organism, often moving in sync with one another.

The first movement of the Mahler opens with the main theme played on a tenor horn, which is like a regular French horn on steroids. In Disney Hall, it sounded amplified with a strong, deep and rich tone, which was only a harbinger of things to come. The opening adagio of the first movement, punctuated by the tenor horn, is tragic, but then it transitions to an allegro in which the main theme appears in many guises and with many Mahleresque melodies which Rattle massaged with loving care.

The second and fourth movements are titled Nachtmusik I and Nachtmusik II, respectively. This explains why the symphony is sometimes referred to as “The Song of the Night.” Together these two movements, with the scherzo, which Mahler marked schattenhaft (shadowy), sandwiched in between, are all about the night. Nachtmusik I (perhaps inspired by Rembrandt’s painting “The Nightwatch”) and the scherzo are dark and eerie sounding, while Nachtmusik II (marked amoroso, or lovingly) is almost chamber music-like with its reduced instrumentation and addition of a guitar and mandolin, which give it more of a serenade feel. It harkens back to the second movement of the composer’s fourth symphony.

The rondo-finale begins with a flurry of timpani and brass and is like the first movement in length, but instead of depicting night and portending tragedy, it announces daybreak and glory. This is evident in the key of C major. The extensive movement ends with an unusual addition of a G# to the C major chord dropping to piano before ending with a fortissimo C major eighth note.

Rattle and the Berlin Philharmonic did not disappoint the sold-out crowd at Disney Hall who roared at the conclusion of the Mahler until the orchestra itself began to get up and leave. It was a rare treat for LA classical music fans. Their performance of the Mahler was worth whatever one had to pay or however far one had to drive to hear it.

—Henry Schlinger, Culture Spot LA

For information about upcoming concerts, visit www.laphil.com.