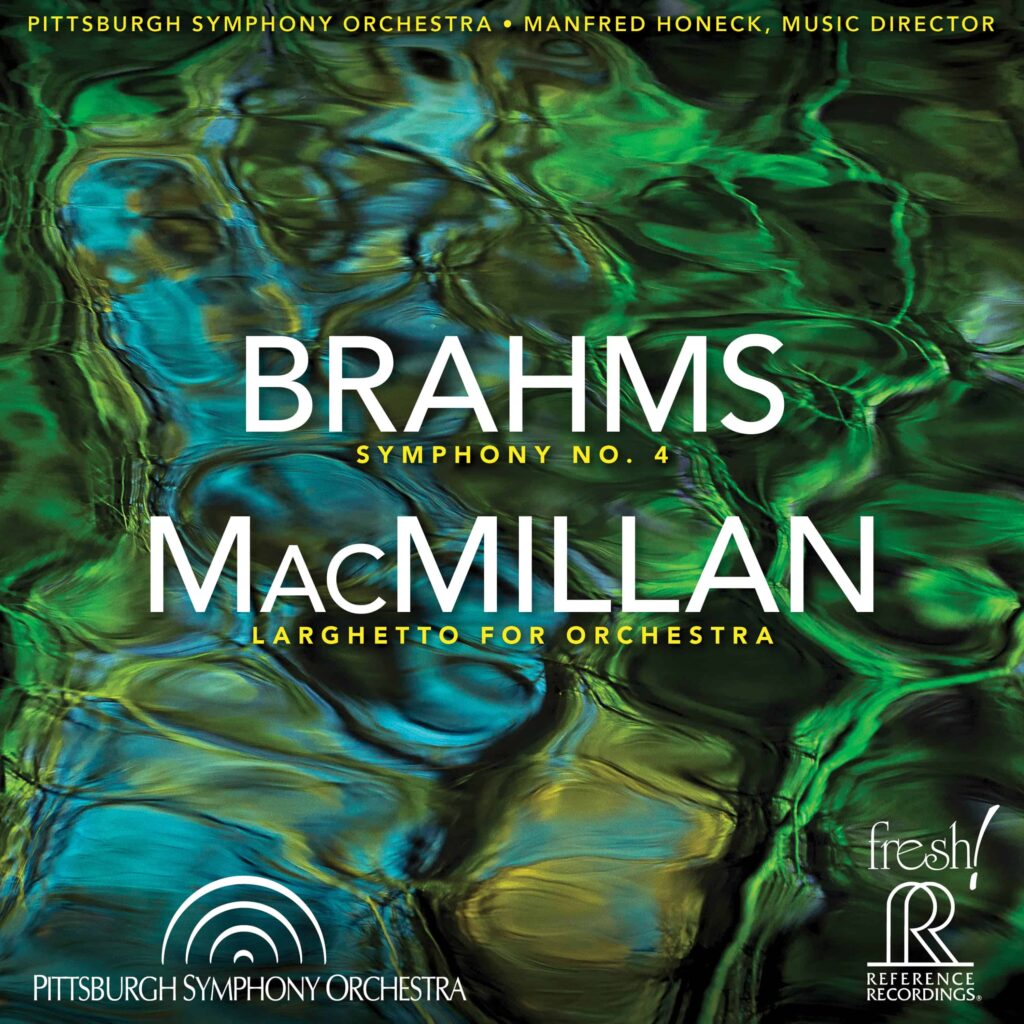

Opening and listening to a new CD by Manfred Honeck and the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (yes, I still listen to CDs) is always exciting because although I never know exactly how Honeck will interpret a work, especially a warhorse that has been recorded too many times to count, I know there will be some surprises.

In the PSO’s latest recording of Brahms’ Symphony No. 4, the listener doesn’t have to wait long for the first surprise, which comes in the opening two notes of the first movement — from a B quarter pick-up note to G half note — in the violins. Honeck lingers ever so slightly on the pick-up note, which confuses the listener momentarily about the allegro non troppo tempo. It’s a different approach than any other version I’ve heard. Honeck then repeats this slightly lingering B in the violins at the first return to the A section.

After that, Honeck’s approach is pretty true to Brahms’ form until the coda where, as Honeck writes in the detailed liner notes that always accompany his recordings, “…it was important to give the tempo rather free rein. Brahms has designed this final passage with dramatic purpose. The music has an incredibly propulsive feel to it. There seems to be no escape, and the movement comes to a close with the greatest force.” Honeck speeds the coda up just slightly. When I first heard it, I was afraid he was going to overdo it, like I believe he did at the end of the Tchaikovsky Fourth. But, in this case, he didn’t allow the tempo to get out of control, and his “free rein” tempo added more drama to an already dramatic first movement.

Those used to Honeck really bringing out the fireworks will be pleasantly surprised with the second movement. As he states in his liner notes, “The second movement is a vocal movement.” He also reminds us that Brahms was a choir director at the time he wrote this symphony. So, Honeck has the orchestra maintain a cantabile (smooth singing style) throughout, which provides a calming interlude between the two dramatic outer movements and the boisterous third movement.

Honeck moves the third movement, allegro giocoso, along a rapid clip, but not too much so. In the section just before the coda, the timpani play approximately 25 measures of dotted sixteenth and eighth notes (bada dum, bada dum), which, even though written as pianissimo, Honeck makes clearly audible to give that section a dance-like feel.

The fourth movement is Brahms at his variation best. Brahms borrows the baroque passacaglia form, in particular, from Bach. The movement contains 30 variations on an eight-bar theme, which Brahms weaves together in an ingenious manner and which gives Honeck and the PSO the chance to be a little freer with the tempos and dynamics. The flute solo by Principal Flutist Lorna McGhee is a thing of beauty ending on the most barely audible note. As he is wont to do, Honeck speeds up the final section just slightly to achieve “the greatest possible drive, urgency, and vehemence” and the maximum dramatic effect.

As with all of Honeck’s recordings with the PSO, this recording of the Brahms fourth symphony has many subtle and some not-so-subtle Honeck touches, mostly with dynamics either of individual instruments or entire sections. Collectively, Honeck and the PSO put their own unique fingerprint on this great symphony.

This disc concludes with the Larghetto for Orchestra by Scottish composer James MacMillan. The piece was composed to celebrate the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Honeck’s tenure as music director with the PSO. At first glance, the Larghetto seems to be an odd piece to celebrate anything because it is, well, a larghetto, which means it is to be played slowly. One thinks of celebratory pieces as lively and fast paced. The composer in the liner notes describes the piece as having a “sad and lamenting character.” I hope Honeck doesn’t take it personally.

That said, the Larghetto is a very traditional composition with hints (at least for this reviewer) of Bruckner, Copland and even Respighi (the solo trumpet played at different times over quiet strings and brass). It is an interesting companion piece to the Brahms; after the sturm und drang of the Brahms, MacMillan’s Larghetto for Orchestra provides almost 15 minutes of calm and reflection.

The PSO has been one of the great American orchestras for decades, and Honeck is the ninth in a long line of all-star conductors, including Fritz Reiner, William Steinberg, Andre Previn, Lorin Maazel and Mariss Jansons. After 10 years at the helm, it is safe to say that the PSO is now Honeck’s orchestra, and he has maintained its elevated status in the orchestral world.

Finally, a review of a CD by the PSO would be incomplete without mentioning that the performances are recorded live from Heinz Hall in Pittsburgh. The sound on these recordings is always astounding. Therefore, a shout-out to Soundmirror and the recording engineers is in order.

Between Brahms and MacMillan, Honeck and the PSO, and the recording engineers, this is a recording not to be missed.

—Henry Schlinger, Culture Spot LA

Listen and learn more at:

https://referencerecordings.com/recording/brahms-symphony-4-macmillan-larghetto/