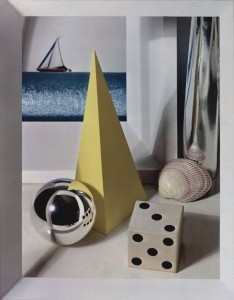

"Images de Deauville" by Paul Outerbridge

Something about “Images de Deauville,” the poster image for the “Paul Outerbridge: Command Performance” exhibit at the Getty, instantly drew me in. The 1936 photograph is an unusually striking, intensely colorful still life. In the foreground are a metallic sphere, a yellow cone, and a single die. Behind those geometric objects, a pink scallop shell, slender silver vase, and framed picture of a sailboat evoke the atmosphere of the French beach/resort town named in the title.

While the attraction was instant, I couldn’t immediately put my finger on what was so impressive about the image – the almost De Chirico-like juxtaposition of objects; the perfect, intricate Escher-like reflections in the sphere and the vase; the play of light and shadow; the exquisite composition?

Then it dawned on me: The fact that I thought of De Chirico and Escher meant I was looking at this image as a painting or drawing. I was seeing it as something that was not quite reality. Indeed, “Images de Deauville” seems too beautiful to be real; but because it is a photograph, it may be more accurate to say it’s hyper-real.

Outerbridge once said: “Art is life as seen through man’s inner craving for perfection and beauty – his escape from the sordid realities of life into a world of his imagining.”

Though skilled as a painter and illustrator, Outerbridge made his name in photography. He studied at the Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York in the early ’20s, and success came quickly. He sold prints to magazines like Vanity Fair while still a student. In 1929, some of his work was included in an international exhibition and acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Fine Art.

Photography in the’20s and ’30s (and even into the ’60s) had yet to reach the artistic status of painting, and the only real market for it was in advertising. Outerbridge, with his keen understanding of artistic technique, was among a small group of photographers that revolutionized print advertising.

In the Getty exhibit, which spans his career and features more than 100 photographs, we see how Outerbridge aspired to the level of fine art with his work. His technical and formal excellence is evident in his Cubist and Surrealist-influenced black-and-white photographs from the ’20s; his color images that appeared in various magazines, including Harper’s Bazaar and Vanity Fair, in the ’30s; and his controversial nudes.

It’s interesting to note that Outerbridge used a die in “Images de Deauville,” an item associated with games of chance. But, as Glynnis Reed, the museum teacher who led me on a tour of the exhibit, pointed out: “Outerbridge doesn’t leave anything to chance.”

Outerbridge planned his photos, meticulously preparing the objects, lighting, and composition. He even built “sets,” like the potting shed he constructed from weathered wood, pots, plants, gardening tools, and even an old window from a barn for a magazine ad.

“The majority of Outerbridge’s photographs were built rather than taken,” said Paul Martineau, assistant curator for the Getty Museum’s Department of Photographs. “He used the camera to express complex aesthetic ideas and created highly nuanced prints that demonstrated his virtuosity.”

Sometimes he modeled photographs after paintings, as in his 1936 “Dutch Girl” nude after Pablo Picasso. His 1937 “Kandinsky” still life includes the tools of his trade like a darkroom timer and folding ruler (and a bottle of vermouth) in a composition that resembles the abstract designs of the Russian painter.

His ’20s platinum and palladium prints are like miniature paintings. Outerbridge called some of them “Semi-Abstractions.” A Saltine box is transformed into a Cubist artwork simply with light and shadow, while a nude on a sofa has the soft, romantic look of an Impressionist painting.

In the ’30s, Outerbridge perfected the Carbro process, a new, highly complex technique for creating color prints from black-and-white negatives. Not only was it time-consuming (taking as long as 10 hours for one print), but it was also expensive (one print costing as much as $150). The intense and highly realistic colors are apparent in his still lifes for magazines, like “Tools With Blueprint” for House Beautiful magazine, and in his nudes, which capture true flesh tones.

His series of voyeuristic nudes and fetishistic nudes, like the disturbing 1937 “Woman With Claws” featuring a naked woman wearing gardening gloves with knives at the fingers, were controversial at the time. Certainly, nude photography was taboo and there was no market for it. Outerbridge said photographing nude models was, except for the “aesthetic enjoyment,” a difficult, expensive, and “thankless job.”

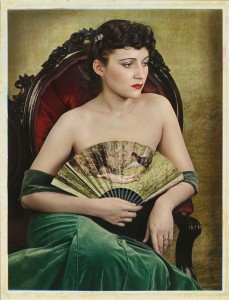

"Girl With Fan" by Paul Outerbridge

“Girl With Fan” is another fine example of Outerbridge’s attention to aesthetic details and his skill with the Carbro color process. The ornate chair with its lush maroon fabric and the rich forest green velvet of the model’s dress add a sense of classic beauty to the image. And the repetition of curves – in the chair, the model’s shoulders, and the fan – make for a lovely composition. Pictured on the fan, the body of the boy lying in the grass actually curves upward, suggesting the shape of the breasts hidden behind the silly image of chickens pecking at a snail on his bottom. The 1936 photograph has a beauty that could seemingly only have been created with a paintbrush, and that’s the magic of Outerbridge’s work.

The exhibit continues through Aug. 9 at the Getty Museum, www.getty.edu.

Check back for information on exhibits and events related to this show.

Photo credits:

“Images de Deauville,” 1936, by Paul Outerbridge/copyright Paul Outerbridge Jr./©2008 G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA/Gift of Mrs. Ralph Seward Allen, Museum of Modern Art, 1942, New York, NY, 174.1942/digital image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

“Girl With Fan,” 1936, by Paul Outerbridge/copyright Paul Outerbridge Jr./©2008 G. Ray Hawkins Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA/Gift of Mrs. Lois Outerbridge, Museum of Modern Art, 1970, New York, NY, 562.1970/digital image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY

Great post! Just wanted to let you know you have a new subscriber- me!