Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art

At the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, you can stroll more than a dozen gardens with 14,000 varieties of plants, stopping to smell the jasmine, contemplate bonsai, or snap a photo in a grove of palm trees — all under the glorious California sun. But Curator Jessica Todd Smith is hoping the new Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art will lure you indoors.

When Smith led a press tour before the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art opened on May 30 after an extensive renovation, she excitedly pointed out some of the highlights of the collection (which began in 1979 with 50 paintings and now totals more than 9,400 objects) and recent acquisitions. The new exhibit space, a combination of the 1984 Virginia Steele Scott Galleries and the 2005 Lois and Robert F. Erburu Gallery, provides more than 16,000 square feet for the American art collection. Painting, sculpture and decorative art from the late-17th to the mid-20th centuries are arranged chronologically in thematic rooms.

The new galleries, with their high ceilings and bright, airy rooms, breathe life into the works, many of which could seem old and stuffy in a less fresh and contemporary setting. Also, Hal Nelson’s artful arrangements of the collection’s decorative arts bring deserved attention to silver, furniture, and ceramics.

Works of the Arts and Crafts movement

Inside the main entrance across from the Rose Hills Foundation Conservatory for Botanical Science, visitors are greeted by a thistle-themed stained glass window by George Washington Maher set in the wall so it is literally a window onto an Arts and Crafts-themed room, where a Frank Lloyd Wright dining table and chairs are displayed.

In a room devoted to 19th-century marble sculpture, walls painted a decorator olive green provide a perfect backdrop for Harriett Goodhue Hosmer’s work, a definite highlight of the galleries. Hosmer’s “Zenobia in Chains,” which reigns over the space, was a coup for the Huntington, when John Murdoch, director of art collections, discovered it at auction in London. It hasn’t been on display since the early 20th century and was considered lost or destroyed until it turned up in a private collection. The 1859 sculpture is regarded as Hosmer’s greatest work.

"Zenobia in Chains"

The artist chose to depict the Syrian ruler at the moment she was led through Rome in shackles. Yet as Smith pointed out, Zenobia is “not defeated; she has taken ownership of her captivity.” Her captor Aurelian actually freed her because he was so impressed by her strength, an attribute Hosmer captures in the nearly 7-foot-high sculpture’s majestic posture. The artistry, from the intricacies of the queen’s robe and its buttons and embellishments down to her toes, is remarkable — so remarkable, in fact, that some journals at the time claimed it couldn’t have been done by a woman. Hosmer’s “Puck” sculpture, another work of extraordinary detail, is exquisitely installed beneath a skylight.

Another recent acquisition, actually a gift, is Samuel L. Francis’ 1980 abstract expressionist painting “Free Floating Clouds,” a 10-by-20-foot canvas that takes up an entire wall. It can’t be missed, and shouldn’t be. Smith pointed out that there is nothing else of this scale in the collection and predicted that it may surprise visitors. Indeed, that work and others in the mid-20th-century room by artists such as Robert Motherwell, Edward Ruscha, and Sam Maloof (who died in May) definitely stand out from the rest of the collection. But Smith indicated that the Huntington has no intention of purchasing contemporary works and competing with other institutions in Los Angeles with already impressive collections. So, in order to more fully represent abstraction, there are works on loan, including a fun Edward Ruscha painting from 1965 titled “Bird Drinks Creek Dry, Fish Escapes.”

Though this colorful room is a lively spot in the galleries, the Huntington’s collection is really distinguished by earlier American works. Some of the pieces to seek out include: a Grant Wood drawing, a sailboat painting by Edward Hopper, paintings by Mary Cassatt and John Singer Sargent, Gilbert Stuart’s iconic image (the iconic image) of George Washington (and a fun China service created for him and decorated with an angel and eagle), and a whole room dedicated to the architecture and design of Charles and Henry Greene.

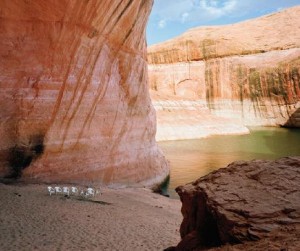

"Davis Gulch, Lake Powell" by Karen Halverson

Finally, the inaugural exhibit in the Susan and Stephen Chandler Wing, designated for temporary exhibitions of light-sensitive drawings and photographs, is “Downstream: Colorado River Photographs of Karen Halverson,” on view through Sept. 28. The color images taken by Halverson during her exploration of the river in the summers of 1994 and 1995, are displayed with some of the first photographs ever taken of the Colorado River culled by Curator Jennifer Watts from the Huntington’s archive, which includes 800,000 photos with an emphasis on the American West.

When Watts saw Halverson’s work years ago, she was immediately attracted to the contrast between “pure beauty and desecration.” Halverson, who now lives in New York State, was at the galleries in May and talked about that idea that permeates this series. “What interests me, what makes me stop and grabs my attention, is the combination of something beautiful and something a little off, a little peculiar, or that symbolically represents the human relationship to the earth,” she said.

A prime example is “Davis Gulch, Lake Powell,” where we see a gorgeous wall of red rock looming over eight white plastic chairs on a small sandy beach. The natural rock formation absolutely dwarfs those seats left, Halverson discovered, by a houseboat invisible to her lens at that moment. Yet the story of the Colorado River is one in which humans seem bent on overpowering nature. Some of Halverson’s other images show the demise of the once-mighty river that has been sucked dry, its water diverted to cities like Los Angeles, Phoenix, and Las Vegas. One photo shows an almost abstract image of a pipeline over baked earth, another of a dry riverbed at the river’s terminus in Mexico. “It’s a poignant story,” Halverson said.

This mixture of old and new in the Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art makes the Huntington’s collection of American art a whole new treasure to explore. Indeed, President Steven Koblick who made some opening remarks before the galleries opened for the press tour, remarked that the Huntington is a “young, dynamic institution.” He added, “When people get a look at these galleries, they’re going to say, ‘This is the Huntington?’”

Photo credits:

The Virginia Steele Scott Galleries of American Art at The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. View toward original Scott Gallery. Credit: The Huntington

Early 20th-century gallery featuring works of the Arts and Crafts movement. Photo: Tim Street-Porter.

Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830–1908), “Zenobia in Chains,” 1859, marble (center) and “Puck,” after 1854, marble (left); Chauncey Butler Ives (1810-1894), “Ruth,” 1853, marble (right). Installation view. Photo: Tim Street-Porter.

“Davis Gulch, Lake Powell,” from the “Downstream” series, 1994–95, archival pigment print,

20 x 24 in., courtesy of the artist.

An amazing accomplishment for the Huntington. Kudos go to Jessica Smith, her staff, and the designers for creating a space that doesn’t dominate the art, but enhances it and becomes part of the exhibit in a subtle way.

Congratulations.