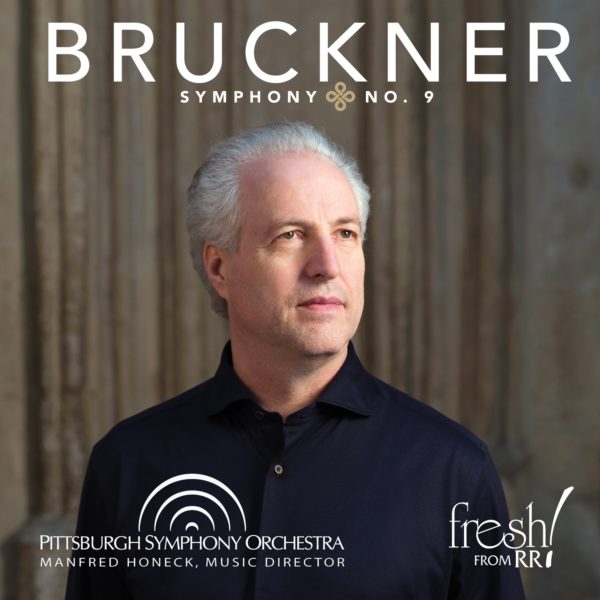

Manfred Honeck, the music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, can apparently read my mind and has been doing so for some time now. He seems to know what I want him and the PSO to record on the spectacular Fresh Series from Reference Recordings. For example, Honeck and the PSO have so far recorded two of my top five favorite symphonies, the Beethoven Third and now, their most recent release, the Bruckner Ninth. But they have previously recorded some of my other all-time favorite symphonies, including the Beethoven Fifth and Seventh, the Bruckner Fourth and the Dvorak Eighth, as well as other favorite works, including three tone poems by Richard Strauss.

Bruckner’s Ninth Symphony is one of two major unfinished symphonies composed by Austrian composers (the other being the Schubert Eighth), although Bruckner did leave a partially completed fourth movement, which he worked on until his death in 1896. And he apparently did not want the symphony to end with the third movement. Maybe I’m just used to hearing only the first three movements (although there have been various attempts to finish and even to record the fourth movement), but it’s hard to imagine the symphony ending any other way than the last few measures of the third movement — peacefully with the horns playing quietly a high F sharp over Wagner tubas and trombones. As Honeck writes about the third — and final — movement, “Most remarkably, this great and sprawling movement comes to an end with three pizzicato (plucked) chords.”

I have to agree with Honeck that Bruckner’s Ninth evokes images from “Bruckner’s world of faith.” Indeed, Bruckner dedicated the symphony “to the beloved God.” One can imagine parts of this monumental symphony played in a cathedral, and Bruckner’s woodwind and brass choirs sound like the church organ that he was expert in playing. Bruckner surely knew his death was imminent, and this symphony could be viewed as a kind of self-epitaph, bringing together elements from his previous symphonies, including his obsession with structure, in a true memorial to his faith and belief in God.

And what about Bruckner’s crescendos? He uses them to their fullest extent and power in this symphony, and this is another area where Honeck excels. He has a seemingly intuitive knack for pulling back on the reins of the orchestra in forte sections just enough to let them gallop into the fortissimo sections.

But as much as Honeck lets the orchestra loose in the fortissimo sections, he can have them play barely audibly as, for example, in the opening d-minor notes of the first movement. And Honeck also exploits the composer’s use of the fermata, which is a musical term for a pause of unspecified length, especially in the third movement, where at times the pause is very long, giving the listener, as well as the musicians, time to take a deep breath.

As with all his recordings with the PSO, Honeck writes the liner notes and gives the listener/reader a play-by-play description of how he interpreted the score with measure numbers and the approximate time in the recording.

Like Honeck’s other recordings with the PSO on Reference Recordings, this recording of Bruckner’s symphonic swan song is a tour de force and belongs in the pantheon of great recordings of this symphony.

—Henry Schlinger, Culture Spot LA

This CD was released Aug. 23. Visit https://referencerecordings.com/recording/bruckner-symphony-no-9/.