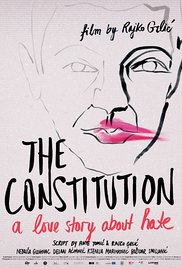

In spite of being shown at an obscure film festival — SEEFF, or South East European Film Festival — and in spite of dealing with the consequences of now-obscure conflicts that two decades ago dismembered Yugoslavia, “The Constitution,” by Croatian director Rajko Grlić, touches your heart and soul — and lingers in your mind longer and deeper than any blockbuster loaded with an overabundance of special effects. The Croatian-Slovenia-Macedonia-Czech-UK co-production richly deserved to win its selection as the SEEFF Best Feature Film and the Grand Jury Prize – Bridging the Borders Award at the 12th annual festival held in LA April 27 through May 4.

Previously, the film won the Grand Prize of the Americas in Montreal 2016, and the Best International Feature Film award in Santa Barbara in January 2017. It was acquired for U.S. distribution by Synergetic and will be released theatrically in the fall.

Billed as a “love story about hate,” it’s a human story with all the ugliness and goodness that comes from being human. The actors look like real people who actually sweat, burp and occasionally pass gas. The audience never wonders if any of the actors “had any work done.” The story, although uncommon, evolves naturally, and one never questions its credibility. The varying pace of the story helps the viewer deal with and alternate between several intertwining stories. No special effects are needed to keep one glued to the screen.

The interwoven and contrasting sequences of good and evil actions feel real. Noble intent is again and again juxtaposed with baser instincts. The noble intent prescribed in the new Croat Constitution (the snippets we hear are quite inspiring) is misused by the Zagreb Police hierarchy to screen out excess Serbs from its ranks — and the spiteful yet invalid father is dutifully cared for by his gay son in spite of the glaring hate the father has for his only child.

It would have been a good guess that this movie’s plot line would stumble under the complex and convoluted history of the Croat Republic and its recent wars, yet the depicted political and homophobic conflicts are elegantly narrated. It’s like discovering a little-known river in the middle of an unkempt yet not too dense forest where you wandered without a map. And guess what? In this setting, the director makes you actually see the forest for the trees.

The noble message that inbred hate can be overcome by decency and persistence gets tempered by the reality that some people are just evil. This is beautifully told in the last scene where a small, yet essential detail can almost be missed. Throughout the movie, the Zagreb police are looking for a bastard who perfidiously kills dogs by placing on sidewalks small sausages laced with broken glass. On three occasions throughout the film, it appears that the culprit is caught (in one humorous instance, the dog poisoner’s mother eats the glass-laced sausage and dies).

The last scene is a happy one. In it, our hero looks out his window at his friends who are leaving on a motorcycle for a well-deserved vacation. The vacationing couple have entrusted him with their little dog that he is gently petting while holding it in his arms. He and the dog look content, and all is well. But as the friends pull away on their bike, on the sidewalk in front of their house one can furtively spot a suspicious-looking character drop a sausage in front of a Weimaraner who nabs it without its owner noticing. The message: In spite of all we try and do, evil is still with us.

—Ekphrasis Rex, Culture Spot LA