For some years now, the Da Camera Society has been presenting Chamber Music in Historic Sites, where pre-modern music is performed in distinctive venues from Pasadena to the Westside. On March 10, Angelenos were treated to Catalan violist extraordinaire Jordi Savall performing solo at the Doheny Mansion. If you can find any excuse to wander into the Doheny Mansion (which now is part of Mount Saint Mary’s College, near USC), you ought to do so. As you approach the mansion walking along Chester Place, you feel like you have entered a sort of time warp: stately 19th-century homes, broad lawns and towering old trees line the street and you half expect velocipedes and four-in-hands to begin arriving at some nearby band shell for the concert.

For some years now, the Da Camera Society has been presenting Chamber Music in Historic Sites, where pre-modern music is performed in distinctive venues from Pasadena to the Westside. On March 10, Angelenos were treated to Catalan violist extraordinaire Jordi Savall performing solo at the Doheny Mansion. If you can find any excuse to wander into the Doheny Mansion (which now is part of Mount Saint Mary’s College, near USC), you ought to do so. As you approach the mansion walking along Chester Place, you feel like you have entered a sort of time warp: stately 19th-century homes, broad lawns and towering old trees line the street and you half expect velocipedes and four-in-hands to begin arriving at some nearby band shell for the concert.

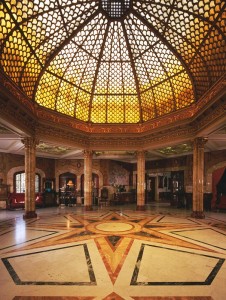

The reality is actually better: You enter the biggest and best house on the block and suddenly you are in an interior straight out of the gilded age. Ticketholders are free to wander about the expansive downstairs (especially to admire a group of paintings depicting the five senses) until they are ushered into the grandiose Pompeian Room to be seated. This is a dramatic circular space with a colonnade of Corinthian columns supporting an impressive stained glass cupola. Floors, walls and columns are of multi-patterned marble set off by intricate wood carvings, gilded frippery and backlit stained glass ceilings in the corners. In short, a delightful space in which to contemplate the unique sounds of the viola da gamba.

Jordi Savall, now in his late 60s, is probably the preeminent modern master of this largely forgotten relic of the Baroque period with over 170 recordings to his credit. As Savall explained it, the viola da gamba developed as a kind of hybrid instrument somewhere between a lute and a modern cello. Some players held in their arms to play it while others held in between their legs, hence the Italian name ‘gamba.’ It was plucked as often as it was bowed. About 1790, the instrument was superseded by the cello and its techniques became lost to time. Savall pointed out that, while he was lucky enough to have a mentor and teacher, his teacher in the mid 20th century had no one to learn from, as all had been forgotten and so he had to learn everything from scratch.

With his wire-rim glasses, close trimmed gray beard, and jacket and turtleneck, Savall looked for all the world like an academic, and began like one by taking the audience on a didactical tour of the history and usage of the viola da gamba, in which he talked about both his equipment — a 7-string made in London by Barak Norman in 1697 — and the variety of playing techniques we would hear. This program was titled La Voix Humaine — the human voice — and refers to the traditional affinity the viola has with the human voice. He demonstrated how each of the seven strings represented the various ranges that are well known to singers, with the highest range being akin to children’s voices.

The musical program consisted of a range of pieces that highlighted not only the various sounds and playing techniques of a viola da gamba, but also the differing styles of composition from many of the Baroque masters of the instrument. He began with three pieces from German composers including J.S. Bach and Karl Friederich Abel that demonstrated how some artists transposed pieces originally written for other instruments like the lute to the viola da gamba. It was fascinating to hear the runs — both plucked and struck percussively with the bow — that made explicit the connection between the viola and a variety of plucked instruments of the Baroque period.

The next musical grouping spotlighted the greatest French viola da gamba masters like Sainte Colombe (father and son) and Marin Marais, who were featured in the 1991 film Tous les Matins du Monde, for which Savall performed and wrote additional music. Savall showed his virtuosity with techniques including multi-string strumming, bouncing the bow on the strings and complex left-handed pizzicato moves. After intermission, Savall turned to a variety of earlier English compositions that, with different tunings, sounded lighter and more dance-oriented than the more cerebral music of the French and Germans. He finished with an anonymous 1580 composition that mimicked bagpipe music.

Savall and the Da Camera Society should be applauded for a program that gives audiences so much more than simply a sublime performance. They also get scholarship, musical discovery, and the chance to experience it all in a superb space. From now until the end of the season in early May, music lovers can take advantage of nine more performances of early classical chamber music in a variety of interesting sites around town. It’s a great way to enhance your musical enjoyment.

For more information, contact the Da Camera Society at (213) 477-2929 or visit www.dacamera.org.