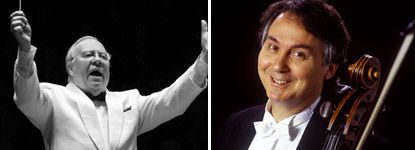

On March 15, Estonian conductor Neeme Järvi conducted the first in a series of concerts as part of the Piatigorsky International Cello Festival featuring the Cello Concerto in B minor by Dvorák with soloist Ralph Kirshbaum and the Symphony No. 5 in D minor by Shostakovich. Also on the program was the Carnival Overture by Dvorák.

Maestro Järvi repeats the concerts at Walt Disney Concert Hall on Saturday, March 17, and Sunday, March 18, with different works for the cello: the Cello Concerto No. 1 in E-flat major by Shostakovich with Mischa Maisky (on Saturday at 8 p.m.) and the Variations on a Rococo Theme by Tchaikovsky with Alisa Weilerstein (on Sunday at 2 p.m.).

The inaugural Piatigorsky International Cello Festival was organized by the USC Thornton School of Music and the LA Phil in partnership with The Colburn School and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra. The finale on Sunday, March 18, at 7:30 p.m. will feature more than 100 cellists onstage at Disney Hall for the West Coast premiere of Rapturedux by Christopher Rouse.

The concert on March 15 opened with the Carnival Overture, one of three overtures Dvorák wrote in honor of his homeland. (The other two are In Nature’s Realm and Othello.) The overture is a brilliant 10-minute orchestral showpiece and is difficult not to be a crowd pleaser.

Järvi conducted it briskly, but without much feeling. And he used a score, which is puzzling considering he’s recorded the piece and probably performed it more than a few times in his long and illustrious career. Because the piece is so short, his frequent and sometimes furious page turning was a distraction. Kudos to Principal Percussionist Raynor Caroll for some outstanding tambourine playing.

In the Dvorák Cello Concerto, Texas-born Kirshbaum showed why he is still one of the preeminent cellists, playing with strength but also sensitivity. Some cellists seem to labor playing the piece; for Kirshbaum, the cello seemed to be an extension of his voice. He obviously knew the piece well, playing most of it without looking at the fretboard.

But the orchestral accompaniment was off and on. The first movement seemed choppy, and Maestro Järvi seemed to have difficulty finding the right balance between the orchestra and the cello. For example, the woodwinds were frequently too loud and yanked one’s attention from the cello. Admittedly, the acoustics in Disney Hall make it a tough nut to crack in this regard. Also, unless one is sitting in the front orchestral section, there are times when it is simply impossible to hear the soloist.

The second movement was better, perhaps because the orchestral accompaniment during the cello part was quieter and more sustained. And in the third movement, Järvi began to find his footing in the Hall and he smoothed out some of the rough edges heard in the first movement.

The second half of the program, though, was quite different than the first half. One reason might have been that most of the principals who did not play in the first half were onstage. But Järvi himself seemed to be more at home with the Shostakovich. It was really a moving performance of a wonderful concert piece.

All four movements have different tempos and feelings, yet each is connected both musically and in terms of instrumentation. The moods range from serious (in the first movement) to one of anxious jocularity (in the Allegreto), to solemn (in the third movement) and, finally, to march-like and glorious (in the Finale). But transcending the different terrains of these movements is Shostakovich’s use of certain instruments, including the xylophone (played expertly again by Caroll), harp and celesta.

At times, Järvi let the orchestra play without much direction, and at other times he used his hands not so much to provide the tempo, which he did more in the Cello Concerto, but to give nuance to the sound. Even though he also used a score in the Shostakovich, one hardly noticed because Järvi was as moved by the music and the LA Phil’s performance as the audience.