Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Jean Sibelius was the most popular composer then living in the Anglosphere, not to mention in his native Scandinavia. Fame was a double-edged sword for the notoriously self-critical composer. Doubt, its flames stoked by alcoholism, gnawed away at his creative drive, aggravated further by the disdain of the modernists then in the ascendent.

“On Sibelius as composer one should waste as few words as on such amateurs,” Theodor W. Adorno wrote. “If [his music] is good, this invalidates the standards of musical quality that have persisted from Bach to Schoenberg.”

A later critic was more direct: “the worst composer in the world,” proclaimed the conductor and musical theorist René Leibowitz.

Sibelius would live on for over 30 years after the premiere of his last major work, Tapiola, but the infamous “silence of Järvenpää” which effectively ended his creative career had already begun.

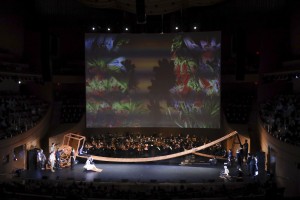

What trajectory his music would have later ventured upon we’ll never know, but glimpses of some visionary new terrain flash before the listener in his incidental music to Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a commission from Denmark which would become his penultimate major score. A rare performance by the Los Angeles Philharmonic of the complete music (a couple minor cuts notwithstanding), under Principal Guest Conductor Susanna Mälkki, was heard last week (Nov. 8-10) at Disney Hall, semi-staged by the Old Globe of San Diego.

Sibelius often is unfairly pegged as being “conservative,” “accessible,” even “safe.” But how to reconcile that reputation with the beautifully cryptic or just plain weird moments which abound in his eclectic Tempest music? The wan allure of the “Dance of the Sylphs,” undercut by its tendency to teeter eerily into the minor; the spectral majesty of the numbers associated with Prospero; the wild braying of the Caliban music; the heart-pounding fear embodied in the storm music.

One regretted that the hall’s microphones recorded Mälkki’s middling Mahler Fifth from the week prior. How better it would have been had they captured her here in her element, despatching the score with a well nigh magical ease that would have made Ariel envious.

The various delicate textural and coloristic details in this score blossomed unforced. Winds and strings interplayed pellucidly, while the Los Angeles Master Chorale was heard in their brief parts with their typical blend of transparency and body. The vocal soloists (Elizabeth DeShong, Ying Fang, Timothy Mix, Jarrett Ott and Joshua Wheeker) sounded attractive enough, if slightly underpowered.

Part of that problem may have been exacerbated by the nature of the semi-staging itself. Although employing a minimalist setup, the field of action was large enough to require pushing the orchestra away from the audience, which resulted in Sibelius’ music kept at an unflattering distance from the stage action (which enjoyed the benefit of being projected by the hall’s loudspeakers). Mälkki and the Los Angeles Philharmonic coped with this challenge gracefully, nonetheless.

It would have been better still to have dispensed with the staging altogether. Like Shakespeare’s Tempest itself, Sibelius’ score is the sort of work that best unfurls across the stage of the mind. So vivid and telling, it’s a score that can power itself on its own aesthetic logic.

One could imagine Sibelius, Prospero-like, confiding to his audience, as he draws the curtains down not only on this score, but his remarkable creative life as well: “So. Lie there, my art.”

—Néstor Castiglione, Culture Spot LA

Visit www.laphil.com.