Ingres' "Comtesse d'Haussonville" is on view at the Norton Simon Museum.

You probably recognized her, or thought you did, even if you didn’t know who she was or who had painted her. She appeared in full color on the cover of Life magazine in 1937, though that’s probably not where you saw her. As one early critic noted, she is “one of those images that appear in dreams.”

She is the “Comtesse d’Haussonville,” painted by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780-1867) in 1845. You can meet her at the Norton Simon Museum through Jan. 25, 2010, while she is visiting California for the first time as part of an art exchange program with The Frick Collection in New York City.

Like the Mona Lisa, the Comtesse is worth the visit alone – though an impressive related exhibit at the Norton Simon, “Gaze: Portraiture After Ingres,” surveys portraits from the early 19th century to the present. She is, in the words of Associate Director and Peter Jay Sharp Chief Curator of The Frick Collection Colin Bailey, one of the most “compelling and beguiling” portraits of the 19th century.

Unlike the Mona Lisa, it is far easier to spend some quality time with the Comtesse. Presumably the crowds in Pasadena won’t be as unrelenting as those basking in the Mona Lisa’s smile at the Louvre, but even if they are, the Comtesse is a large painting (approximately 4-by-3 feet as opposed to the Mona Lisa’s 30-by-20 inches) that doesn’t require being right on top of it to admire it.

The painting of 27-year-old Louise-Albertine de Broglie, a French aristocrat who was married to Vicomte Othenin d’Haussonville in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, appropriately commands a room in the European art galleries, flanked by two of Ingres’ drawings, also on loan from The Frick Collection (one a study for the “Comtesse” and another for his history painting, “The Golden Age”). “She is in good company,” pointed out Carol Togneri, chief curator of the Norton Simon Museum at a press event with Bailey. The painting is installed with the Norton Simon’s Ingres portrait of Baron Joseph-Pierre Vialetes de Mortarieu (1805-06) and large-scale noble portraits, including one of a countess, by other artists.

Though Ingres considered portraiture a less noble endeavor than his history paintings, Bailey said, he is famous as a master of that form. One look at the Comtesse says a thousand words about why. The Comtesse has most likely just come back from an evening at the opera; she was a music lover and a pianist who knew Chopin. Her ice-blue silk cocktail dress, red hair ribbon and gold and turquoise jewelry, as well as the calling cards, opera glasses, evening bag, porcelain and flowers on the velvet-draped mantel behind her are rendered in exquisite detail. Bailey pointed out that there is luminous light and practically a rainbow of blues in the portrait. Her gaze is very thoughtful, perhaps reflecting the fact that she was a writer of romantic novels and a biography of English poet Lord Byron. Her left hand is held beneath her chin in a contemplative fashion. It’s a “canonical” pose from ancient Roman sculpture and definitely part of what makes the portrait particularly striking and memorable.

Bailey noted that Ingres contemplated the portrait for three years and probably made as many as 80 preparatory drawings, 16 of which are known, before working on it intensively between January and June 1845.

Yet, despite the seeming perfection of the portrait, Ingres abandoned reality to suit his artistic needs – the Comtesse’s reflection is visible when it shouldn’t be, her right arm seems to originate from her ribcage rather than her shoulder, her fingers appear to have no bones. That approach would appeal to avant-garde artists like Picasso who played with reality and abstraction, said Leah Lembeck, the assistant curator at the Norton Simon who organized “Gaze: Portraiture After Ingres.”

The exhibit features 150 paintings, sculpture, etchings and photographs, mainly from the Norton Simon collection. In addition to the exquisite portrait of Jeanne Hebuterne by Modigliani, a wonderful watercolor-and-ink work by Klee, a Warhol self-portrait, Van Gogh and Picasso etchings, and Duchamp’s take on the Mona Lisa, there is an interesting section of portraits of famous artists by famous artists.

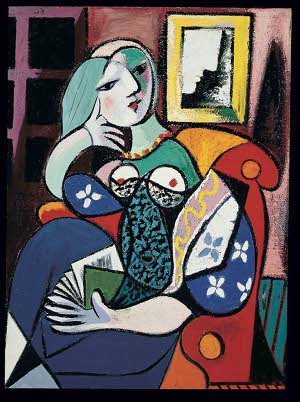

Picasso's "Woman with a Book" is part of a new exhibit on portraiture at the Norton Simon Museum.

Ingres influenced generations of artists, including Seurat, Degas and Renoir. But of all the artists represented in “Gaze,” Picasso was the most visibly influenced by Ingres, Lembeck noted. (In turn, Picasso had the greatest influence on portraiture of any 20th-century artist.) In the gorgeously colorful and textured “Woman with a Book” (1932), he transforms Ingres’ 1856 portrait of Madame Moitessier into “a dreamy portrait” of his mistress and muse Marie-Therese Walter, Lembeck said. A small photo of the Ingres painting allows comparison.

“Gaze” reveals the history of portraiture from the 19th century, as artists moved away from paid commissions and were free to experiment with style. Those styles are so various that it’s easy to forget that the works on display have a significant feature in common. If you were to think about how many ways a portrait could be executed, you would never imagine everything you will see in this exhibit.

Edgar Munhall, curator emeritus from The Frick Collection and the man who literally wrote the book on the “Comtesse,” will give a lecture on Saturday, Nov. 7, at 4 p.m. at the Norton Simon Museum. Visit the museum’s website for other lectures and events related to the “Comtesse” and “Gaze.”

Image credits:

“Comtesse d’Haussonville,” dated 1845

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (French, 1780–1867)

Oil on canvas, 51 ⅞ x 36 ¼ inches (131.8 x 92)

The Frick Collection, New York

Photo: Michael Bodycomb

“Woman with a Book,” 1932

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881-1973)

Oil on canvas

51-3/8 x 38-1/2 in. (130.5 x 97.8 cm)

The Norton Simon Foundation, F.1969.38.10.P

© 2009 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York