The new show at the Getty Villa, The Last Days of Pompeii, refers variously to an event, a book, and a rich history of mythmaking. The event, of course, is the A.D. 79 eruption of Mount Vesuvius outside Naples that buried the prosperous Roman town. But if you come expecting to see a display of artifacts from the Pompeii excavations, you will be sorely disappointed as there are only a handful of such items. The unexpected, but nonetheless compelling thrust of this exhibit is to trace the origins and development of Western culture’s enduring popular fascination with the ancient tragedy.

The name of the show is taken from a hugely popular 1834 book by Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the British dandy whose name also happens to be attached to the annual Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest in which contestants attempt to dream up the worst possible beginnings to imaginary novels (Bulwer-Lytton began one of his novels with the infamous line “It was a dark and stormy night…”). The enormous success of The Last Days of Pompeii inflamed the popular imagination, and inspired contemporary artists to come up with their own ridiculously over-romanticized concepts of the tragedy, such as the pair of lovely Lawrence Alma-Tadema canvases depicting languid, swooning ladies with a smoking volcano in the background.

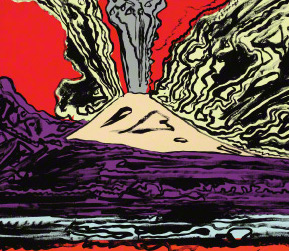

The show is small, comprising only three rooms and a hallway, and is naturally divided into three successive themes: decadence, apocalypse, and resurrection. Each section comprises a mix of artworks from various periods, hence, you will see a Salvador Dalí next to an Ingres, or an Andy Warhol beside a presentation case for Pope Pius IX — all focusing on various aspects of Pompeii. In the decadence section, things are a bit too chaste; nothing there really points to the great amount of explicit erotica unearthed in Pompeii.

Glaucus and Nydia, 1867, Lawrence Alma-Tadema (inspired by the main characters in the 1834 book, Last Days of Pompeii)

This omission is made up for in the apocalypse area with a couple of amusing bits. One is an abstract panel by Mark Rothko for a commission to create murals for the Four Seasons restaurant in New York. Rothko, ever the bomb-thrower, said, “I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.” The murals, which represented a burning city, were never installed. The other fun thing is a selection of old photos depicting a huge spectacle created by impresario James Pain in the late 19th century. Also called The Last Days of Pompeii, it was America’s first “Pyrodrama,” which featured live gladiator battles, circus animals, and a huge stage set of an ancient “Pompeii” which, during the finale, collapsed in a great conflagration augmented with fireworks. This show toured America extensively and could be seen at Coney Island from 1879-1914.

The show also explains how carefully controlled access and advances in technology contributed to the Pompeii-mania. The Bourbon rulers of Naples were in charge of the excavations in the 18th and 19th centuries and held annual fairs, showing off ancient finds that they felt would help to legitimize their own rule. At the same time, the advent of photography allowed detailed visual records of the finds to be disseminated across Europe and America, stimulating great curiosity. Around the same time, an Italian figured out how to successfully create plaster casts of the cavities left by ash-entombed people and animals, adding another fascinating layer of wonder. And when the first train line to Pompeii opened in 1841, the tourists descended and have never stopped coming since.

Each artwork has detailed, well-lit explanations, and there are TV monitors placed about that run loops from various Hollywood films beginning in 1913, all called — you guessed it — The Last Days of Pompeii. There are also artifacts from an 1825 opera of the same name by Pacini. It’s a shame they do not have more actual relics from Pompeii in the show, but the good thing is, you can simply step into the adjoining museum and see many top-quality pieces of Roman art, one of which, a magnificent full-sized bronze statue called “Youth as a Lamp Bearer,” was unearthed at Pompeii and is on long-term loan from the archeological museum in Naples.

If you are on the fence about whether to go see this show, here is another inducement: a fourth-century B.C., larger than life-size sculpture called “Lion Attacking a Horse” is now on display in the rotunda of the Getty Villa, and it is a must-see. This dramatic sculpture, full of energy and movement, was originally mounted in Rome’s Circus Maximus where chariot races and mock hunts took place. It has not left Rome for more than 2,000 years, and now that conservation work is done, it is going back to its permanent place at the Palatine Museum on Feb. 4, 2013. Both exhibits are highly recommended.

—David Maurer, Culture Spot LA

The Last Days of Pompeii continues through Jan. 7, 2013, at the Getty Villa in Pacific Palisades. For more information and reservations, visit www.getty.edu/visit/.

Image credits:

Mount Vesuvius, 1985, Andy Warhol. Screen print on Arches 88 paper, 28 1/2 x 32 in. (72.4 x 81.3 cm). The Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh; Founding Collection, Contribution The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. © 2012 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Glaucus and Nydia, 1867, Lawrence Alma-Tadema. Oil on wood panel, 15 3/8 x 25 5/16 in. (39 x 64.3 cm). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Noah L. Butkin, 1977.128

Lion Attacking a Horse, Greek, 325–300 B.C.; restored in Rome in 1594. Sovraintendenza ai Beni Culturali di Roma Capitale— Musei Capitolini