On Sunday, the Dutch conductor Edo de Waart conducted the LA Phil in three works, The Chairman Dances by John Adams, the Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, Op. 22 by Saint-Saëns with pianist Behzod Abduraimov, and the Symphony No. 3 in A minor, Op. 56 “Scottish” by Mendelssohn.

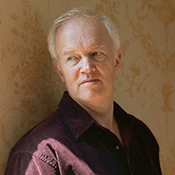

De Waart, looking older than his 74 years, and using a chair to conduct, began the concert with The Chairman Dances by Adams, the current Creative Chair and guest conductor of the Phil, and the former composer-in-residence at the San Francisco Symphony when de Waart was music director. De Waart was the first conductor to record the Dances, so he has witnessed its evolution from its inception as an outtake from Adams’ opera Nixon in China to a standard repertory piece.

With hints of Ravel, Gershwin and Stravinsky, the piece still reflects Adams’ distinctive minimalist writing. De Waart and the LA Phil offered a version of the dances with an almost-Romantic flare, which fit nicely with the rest of the program. He brought out the more melodic lines above the constant percussion and gave the work a more grandiose feel.

The first half concluded with the Saint-Saëns concerto — a Romantic piece with a clear classical foundation — with the 26-year-old Uzbek pianist Abduraimov. Wow! What a performance! Abduraimov played brilliantly, and de Waart offered a restrained accompaniment, never allowing the orchestra to overpower him. And it was a good thing because Abduraimov showed why he is one of the best of the spate of young soloists around. His technique was flawless, without being showy, even though he can run with the best of them. In fact, if the piano had been flammable, the heat generated by Abduraimov’s blazing fingers would have caused it to combust. More importantly, his musicianship displayed a maturity beyond his 26 years. One would be hard-pressed to imagine a better performance of this concerto.

During the performance, I wondered why the Saint-Saëns concertos aren’t programmed more often. They really have everything one could want in a piano concerto: very hummable melodies, demanding piano parts (Saint-Saëns was himself a world-class pianist), beautiful orchestral accompaniment and just the right amount of flare and pizzazz.

After a few curtain calls, de Waart pushed Abduraimov back down on the piano bench for an encore. After the thrilling excitement of the concerto, Abduraimov appropriately chose a contrasting encore, the mournful, ethereal Siciliano from Concerto in D minor, BWV 596 by Vivaldi arranged by Bach.

The concert concluded with a no-frills performance of the Mendelssohn Symphony. This was a lush rendition of this great Romantic symphony. De Waart could have rushed the orchestra, for example, in the lively and energetic scherzo, but he didn’t, taking it at just the right speed so that the orchestra didn’t stumble over itself. And where some conductors take liberties with tempos at the end of the final movement, de Waart played it straight, allowing the stately, majestic theme to speak for itself.

Sitting in a chair did not diminish deWaart’s conducting ability. In fact, one forgets that most of the conductor’s important work occurs before the performance, leaving him or her free to be more of a performer in the concert. De Waart didn’t have to worry about that because he let the music speak for itself. As always, the playing by the members of the Phil was stellar.

—Henry Schlinger, Culture Spot LA

For information about upcoming concerts, visit www.laphil.com.